Nitrate Poisoning

4 min read

Nitrate poisoning in cows happens when they eat feed with high nitrate levels, often in late autumn or winter. This page details how nitrate transforms to nitrite in the cow's rumen and binds to haemoglobin in the blood, stopping it from carrying oxygen, which can lead to rapid death. The page outlines critical nitrate levels in feed, risk factors, how to reduce risk, and symptoms of nitrate poisoning. Additionally, it provides guidance on what to do if you see symptoms in your herd. The page also explains what causes high nitrate levels in plants, including environmental and plant stress factors.

Nitrate poisoning is caused by high nitrate levels in feed and it usually occurs in late autumn or winter, particularly during a flush of growth after a dry period.

| Nitrate-N (%) |

Nitrate-N |

Nitrate (%) | Recommendations |

| Below 0.10 | Below 1000 | Below 0.44 | Safe to feed under all conditions |

| 0.10 – 0.15 | 1000 - 1500 | 0.44 - 0.66 | Safe to feed to non-pregnant animals |

| 0.15 – 0.20 | 1500 - 2000 | 0.66 – 0.88 | Safely fed if limited to 50% of the total DM ration |

| 0.20 – 0.35 | 2000 - 3500 | 0.88 – 1.54 | Feeds should be limited to 35-40% of the total DM ration. Feeds over 2000ppm nitrate-N should not be fed to pregnant animals. |

| 0.35 – 0.40 | 3500 - 4000 | 1.54 – 1.76 | Feeds should be limited to 25% of total DM in the ration. Do not feed to pregnant animals. |

| Above 0.40 | Above 4000 | Above 1.76 | DO NOT FEED. Feeds containing these levels are potentially toxic. |

Adopted from Hill Laboratories

Plants take up nitrate from the soil and then use energy from photosynthesis to convert nitrate to protein for growth. However, if nitrate uptake from the soil is greater than the conversion to protein, then nitrate can accumulate to abnormal levels. This can be caused by several factors:

Soils high in nitrogen readily supply nitrate to plants, this can occur without the addition of nitrogen fertilisers. Soils that have high acidity (lack of lime fertiliser), high N from white clover, sulfur or phosphorus deficiencies (lack of fertiliser); and low molybdenum also increase nitrate uptake by plants.

N fertiliser is only a very small piece of the puzzle and the other factors mentioned above (e.g. natural soil state, plant type and maturity, sunlight, rainfall, temperature, pests) play a much bigger role in the risk of nitrate poisoning. Nitrate poisoning was occurring on farms 60-70 years ago, when little N was used.

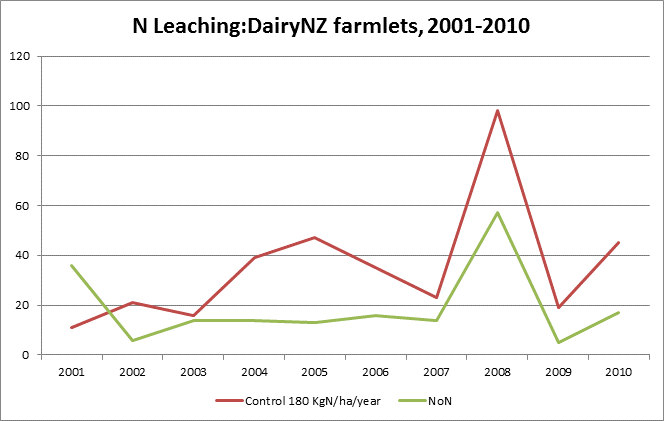

Spikes in nitrate levels can occur when seasonal conditions combine in the autumn and winter, particularly following summers and autumns that are drier than normal (see this graph of DairyNZ’s Waikato farmlets from winter of 2008 and the spike that occurred even for the Low N Farm, green line).

Now’s the perfect time to check in, plan, and set up for a strong season. We’ve pulled together smart tips and tools to help you stay ahead all winter long.

Whether you prefer to read, listen, or download handy guides, we’ve got you covered with trusted tools to support your journey every step of the way.

Put our proven strategies and seasonal tools to work. Boost production, support animal health and watch your profits hum.

Tools that are backed by science, shaped by farmers and made for this season.

That’s Summer Smarts.

Autumn Smarts brings together the research-backed tools that build resilience and boost performance.