Understanding transition cows

3 min read

Managing your cows during the transition from pregnancy to lactation helps prevent diseases and optimises seasonal performance. This period sees the cow's nutrient requirements spike but intake doesn't match up, leading to negative energy balance. Cows compensate by breaking down body tissue for energy. You can't significantly alter this body condition score (BCS) loss after calving. So, focus on proper nutrition management pre-calving and calving at the right BCS. Common diseases in this transition include milk fever, ketosis, and fatty liver, which can be mitigated with targeted care and proper nutrition. Aim for the right BCS to avoid these health issues.

It is important to understand what is happening in the cow and how to best manage her during this period to ensure optimal seasonal performance, and avoid metabolic and infectious diseases.

Substantial physiological changes occur as the cow transitions from pregnancy to lactation. With the onset of lactation, there is a sudden and large increase in nutrient requirements which is not matched by an associated increase in nutrient intake, and the cow enters a stage of negative energy balance immediately post-calving.

To adapt to the negative energy balance immediately post-calving, and provide the necessary energy for milk production, the cow mobilises large amounts of body tissue (primarily fat, with smaller amounts of protein), which is reflected in a loss of BCS.

Little can be done in the first few weeks post-calving to alter this BCS loss. The primary regulators of the performance of the transition and early lactating dairy cow are BCS at calving, and nutrition management pre-calving.

See Feeding the transition cow.

Metabolic disorders occur when the dairy cow cannot successfully adapt to all the physiological changes. These diseases are complex and interrelated. The occurrence of one can increase the risk of another and also predispose the cow to infectious diseases. The most common metabolic disorders that occur during the transition period in pasture-based systems are:

Milk fever generally occurs within the first 24 hours post-calving, but can still occur 2 to 3 days post-calving. It is defined as low blood concentrations or calcium (hypocalcaemia) and can be clinical (<1.4 mmol/L Ca) or, more commonly, sub-clinical (<2 mmol/L Ca).

| ✓ Ensure cows are at target BCS 2-3 weeks pre-calving. - Separate at risk cows prior to calving. | BCS strategies |

| ✓ Understand milk fever and factors that influence it | Milk fever & Down cows |

| ✓ Supplement with magnesium pre-and post-calving | Magnesium |

| ✓ Keep dietary calcium low pre-calving✓ Supplement colostrum cows with calcium | Calcium |

| ✓ Avoid feed high in phosphorus (e.g. PKE) but supplement with phosphorus if diets are low in phosphorus (e.g. fodder beet) | FeedChecker |

| ✓ Avoid grazing effluent paddocks and understand the impacts of DCAD | DGAD |

| ✓ Feed cows appropriately pre- and post-calving |

In early lactation, all cows are in a state of negative energy balance; however, the magnitude of this can vary. When the negative energy balance is severe, the cow metabolises fat at a high rate and converts it into ketones for energy. If ketone production is too high, then the cow may suffer from ketosis.

Ketosis can be divided into three types

See Ketosis for information on diagnosis and risk reduction.

See Down cows for treatment options and hip lifting

Fatty liver occurs when the cow is breaking down too much body fat for its liver to process properly and it becomes clogged with excess lipids. This develops due to fat mobilisation during severe negative energy balance and usually occurs during the first four weeks after calving.

To reduce the risk of fatty liver do not exceed BCS targets

Fatty liver can occur when cows exceed BCS targets and is sometimes referred to as “fat cows’ disease”. If cows are at or greater than target BCS prior to calving, then restricting energy to 90% of requirements for two to three weeks pre-calving can reduce the risk of fatty liver and other metabolic disorders.

Fatty liver can also occur when there is a sudden drop in feed intake. It often arises secondarily to other metabolic diseases, particularly ketosis.

Limited research on fatty liver has been conducted with cows in pasture-based systems.

Currently, the occurrence of fatty liver in pasture-fed cows does not appear to be high; however, in systems where higher levels of supplementary or non-pasture feeds are used, an increase in the incidence of fatty liver has been reported, particularly when cows are above target BCS at calving.

See Down cows for treatment options and hip lifting

See Technote 15 to further understand what causes fatty liver

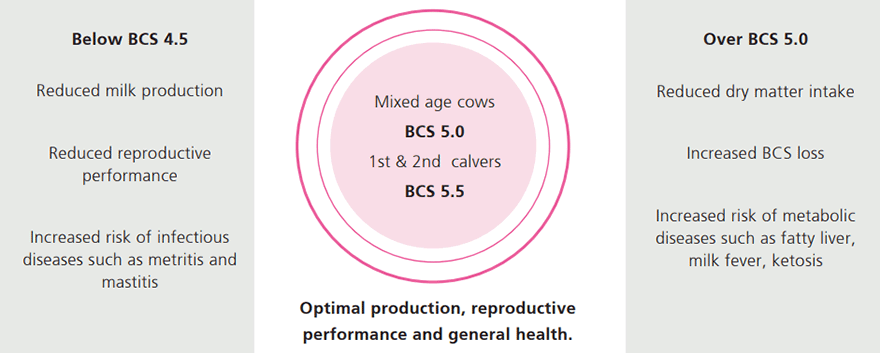

Body condition score targets at calving are set to optimise milk production and maximise reproduction and health. Mixed-aged cows should calve at a 5.0 BCS, while 2 and 3-year olds should calve at a 5.5 BCS. Cows thinner than target BCS have poorer immune function and are at a greater risk of infectious diseases (e.g. mastitis and metritis). They also produce less milksolids and have poorer reproductive performance in the following season. However, cows fatter than target BCS will have a lower feed intake and greater BCS loss post-calving, predisposing them to metabolic disorders such as ketosis, fatty liver and milk fever, especially if they are consuming more than their metabolic requirements in the 2-3 weeks pre-calving.

Figure 1: Effects of not meeting BCS targets at calving

Now’s the perfect time to check in, plan, and set up for a strong season. We’ve pulled together smart tips and tools to help you stay ahead all winter long.

Whether you prefer to read, listen, or download handy guides, we’ve got you covered with trusted tools to support your journey every step of the way.

Put our proven strategies and seasonal tools to work. Boost production, support animal health and watch your profits hum.

Tools that are backed by science, shaped by farmers and made for this season.

That’s Summer Smarts.

Autumn Smarts brings together the research-backed tools that build resilience and boost performance.